Asia Pacific Academy of Science Pte. Ltd. (APACSCI) specializes in international journal publishing. APACSCI adopts the open access publishing model and provides an important communication bridge for academic groups whose interest fields include engineering, technology, medicine, computer, mathematics, agriculture and forestry, and environment.

Frameless cinema: Proposed scale of narrative involvement in virtual reality

Vol 1, Issue 1, 2020

Download PDF

Abstract

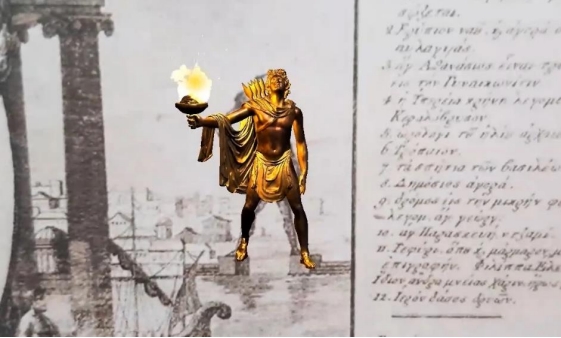

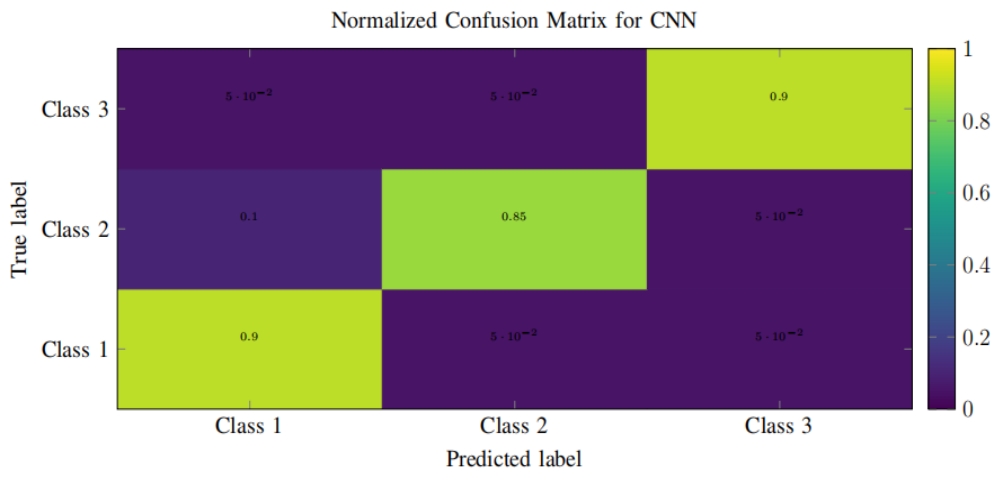

The possibility of recording in 360° has aroused the interest of entrepreneurs and researchers in the potential narrative powers of virtual reality in different fields. However, there are still some questions that have not been sufficiently confirmed, such as the higher level of narrative involvement of the viewer in this new form of storytelling. In order to make up for this lack, this research presents the design of an experimental analysis in different phases. It is a quantitative-qualitative pilot project based on the MNEQ scale[1] that allows us to evaluate and compare the viewing experience of a narrative story through virtual reality presentation and different types of two-dimensional screens to a minimum of 100 people divided into experimental groups. Under the assumption that each treatment or each technology (independent variable) has different impacts on the viewer’s narrative involvement (dependent variable), the aim is to analyze empathy (EP), sympathy (S), cognitive perspective taking (CP), loss of time (LT), loss of self-awareness (LS), narrative presence (NP), narrative involvement (NI), distraction (D), ease of cognitive access (EC) and narrative realism (NR). Four different types of analysis (statistical, variance, observational, open-ended) are included. We offer a new model of self-developed analysis for complete Spanish-language cinematic virtual reality works. The experimental design seeks to establish a comprehensive research model in order to discuss whether virtual reality offers, as it is believed, greater engagement.

Keywords

References

- Busselle R, Bilandzic H. Measuring Narrative Engagement. Media Psychology 2009; 12(4): 321–347.

- Kjær T, Lillelund CB, Moth Poulsen M, et al. Can you cut it: An exploration of the effects of editing in cinematic virtual reality. Proceedings of the 23rd ACM Symposium on Virtual Reality Software and Technology. Gothenburg, Sweden: ACM Press; 2017. p. 1–4.

- Mateer J. Directing for cinematic virtual reality: How the traditional film director’s craft applies to immersive environments and notions of presence. Journal of Media Practice 2017; 18(1): 14–25.

- Sutherland IE (editor). A head-mounted three-dimensional display. Fall Joint Computer Conference, Part I on – AFIPS; 1968 Dec 9–11.

- Burch N. Praxis du cinema (French) [Cinema practice]. Paris: Gallimard; 1969.

- Zunzunegui S. Thinking the image. Madrid: Cátedra; 1998.

- Truffaut F. The cinema according to Hitchcock. 5th ed. Madrid: Editorial Alianza; 2010.

- Ding N, Zhou W, Fung AYH. Emotional effect of cinematic VR compared with traditional 2D film. Telematics and Informatics 2018; 35(6): 1572–1579.

- Appel M, Gnambs T, Richter T, Green MC. The Transportation Scale-Short Form (TS-SF). Media Psychology 2015; 18(2): 243–266.

- Green MC, Brook TC, Kauffman GF. Understanding media enjoyment: The role of transportation into narrative worlds. Communication Theory 2004; 14(4): 311–327.

- Keshavarz B, Hecht H, Lawson B. Visually induced motion sickness: Causes, characteristics, and countermeasures. In: Hale K, Stanney K (editors). Handbook of virtual environments. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2014. p. 648–697.

Supporting Agencies

Copyright (c) 2020 Diego Bonilla, Helena Galán Fajardo

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This site is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0).

Prof. Zhigeng Pan

Professor, Hangzhou International Innovation Institute (H3I), Beihang University, China

Prof. Jianrong Tan

Academician, Chinese Academy of Engineering, China

Conference Time

December 15-18, 2025

Conference Venue

Hong Kong Convention and Exhibition Center (HKCEC)

...

Metaverse Scientist Forum No.3 was successfully held on April 22, 2025, from 19:00 to 20:30 (Beijing Time)...

We received the Scopus notification on April 19th, confirming that the journal has been successfully indexed by Scopus...

We are pleased to announce that we have updated the requirements for manuscript figures in the submission guidelines. Manuscripts submitted after April 15, 2025 are required to strictly adhere to the change. These updates are aimed at ensuring the highest quality of visual content in our publications and enhancing the overall readability and impact of your research. For more details, please find it in sumissions...

.jpg)

.jpg)