Asia Pacific Academy of Science Pte. Ltd. (APACSCI) specializes in international journal publishing. APACSCI adopts the open access publishing model and provides an important communication bridge for academic groups whose interest fields include engineering, technology, medicine, computer, mathematics, agriculture and forestry, and environment.

High school students’ views on the use of metaverse in mathematics learning

Vol 1, Issue 2, 2020

Download PDF

Abstract

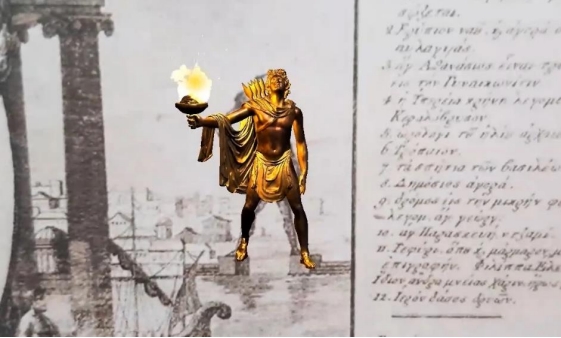

The introduction of information and communication technology (ICT) into the classroom has led to a new learning scenario based on educational innovation, in which mobile devices are used for teaching. In this study, the views of upper middle class students in a private educational institution in Mexico on the implementation of augmented reality teaching strategy based on metaverse mobile application are analyzed. The study is descriptive and survey based. Data retrieval is conducted using a clearly designed digital questionnaire. From August to December 2018, 192 first semester students who participated in the basic mathematics course participated in the course. The results show that compared with the previous academic year, the school recognition index has improved, and the affinity for the use of reality in the classroom has improved. When using the strategies mediated by these tools, the view of learning change is favorable. Therefore, it can be inferred that the application of augmented reality in mathematics teaching is of great help to students’ performance.

Keywords

References

- Santos M, Wolde A, Taketomi T, et al. Augmented reality as multimedia: The case for situated vocabulary learning. Research and Practice in Technology Enhanced Learning 2016; 11(4): 1–23.

- Martínez M, Ferraz E. Uso de las redes sociales por los alumnos universitarios de educación: un estudio de caso de la península ibérica (Spanish) [Use of social networks by university students of education: A case study of the Iberian peninsula]. Tendencias Pedagógicas 2016; 28: 33–44.

- Rangel E, Martínez J. Educación con TIC para la sociedad del conocimiento (Spanish) [ICT for education to the knowledge society]. Revista Digital Universitaria 2013; 14(2): 1–14.

- Bates T. Teaching in a digital age. New York: Routledge; 2015.

- Gómez M, Contreras L, Gutiérrez D. El impacto de las tecnologías de la información y la comunicación en estudiantes de ciencias sociales: Un estudio comparativo de dos universidades públicas (Spanish) [The impact of information and communication technologies on social sciences students: A comparative study of two public universities]. Innovación Educativa 2016; 16(71): 62–80.

- Leguizamón J, Patiño O, Suárez P. Tendencias didácticas de los docentes de matemáticas y sus concepciones sobre el papel de los medios educativos en el aula (Spanish) [Trends teaching math teachers and their conceptions of the role of educational media in the classroom]. Educación matemática 2015; 27(3): 151–173.

- Leung A. Exploring techno-pedagogic task design in the mathematics classroom. In: Leung A, Baccaglini-Frank A (editors). Digital technologies in designing mathematics education tasks. Switzerland: Springer; 2017.

- Santos M, Camacho M. Framing the use of technology in problem solving approaches. The Mathematics Enthusiast 2013; 10(2): 279–302.

- Esparza D. Uso autónomo de recursos de Internet entre estudiantes de ingeniería como fuente de ayuda matemática (Spanish) [Autonomous use of Internet resources among engineering students as a source of math aid]. Educación Matemática 2018; 30(1): 73–91.

- Romeu T, Guitert M, Raffaghelli J, et al. Ecologías de aprendizaje para usar las TIC inspirándose en docentes referents (Spanish) [Learning ecologies to use ICT inspired by teachers]. Revista Comunicar 2020; 28(62): 31–42.

- Almerich G, Suarez J, Diaz I, et al. Estructura de las competencias del siglo XXI en alumnado del ámbito educativo (Spanish) [Structure of 21st century competences in students in the sphere of education. influential personal factors]. Factores Personales Influyentes 2020; 23(1): 45–74.

- Barrera F, Reyes A. El rol de la tecnología en el desarrollo de entendimiento matemático vía la resolución de problemas (Spanish) [The role of technology in the development of mathematical understanding through problem solving]. Educatio Siglo XXI 2018; 36(3): 41–72.

- Tecnológico de Monterrey. Reporte EduTrends. Radar de Innovación Educativa Preparatoria 2016 (Spanish) [EduTrends report. High School Educational Innovation Radar 2016]. Monterrey: Tecnológico de Monterrey; 2016.

- Tecnológico de Monterrey. Reporte EduTrends. Radar de Innovación Educativa 2017 (Spainsh) [EduTrends report. Educational Innovation Radar 2017]. Monterrey: Tecnológico de Monterrey; 2017.

- Domingo M, Bosco A, Carrasco S, et al. Fomentando la competencia digital docente en la universidad: Percepción de estudiantes y docents (Spanish) [Fostering teacher’s digital competence at university: The perception of students and teachers]. Revista de Investigación Educativa 2020; 38(1): 167–782.

- Ferrer J, Torralba J, Jiménez M, et al. AR book: Development and assessment of a tool based on augmented reality for anatomy. Journal of Science Education and Technology 2015; 24(1): 119–124.

- Cabero J, García F. Realidad aumentada: Tecnología para la formación (Spanish) [Augmented reality: Technology for training]. Madrid: Síntesis; 2016.

- Fombona J, Pascual M. La producción científica sobre Realidad Aumentada, un análisis de la situación educativa desde la perspectiva SCOPUS (Spanish) [The scientific production on Augmented Reality, an educational literature review in SCOPUS]. Revista de Educación Mediática y TIC 2016; 6(1): 39–61.

- Lagunes A, Torres C, Angúlo J, et al. Prospectiva hacia el aprendizaje móvil en estudiantes universitarios (Spanish) [Exploration toward mobile learning in university students]. Formación Universitaria 2017; 10(1): 101–108.

- Cabero J, Barroso J, Llorente C. La realidad aumentada en la enseñanza universitaria (Spanish) [Augmented reality in university education]. Revista de Docencia Universitaria 2019; 17(1): 105–118.

- Seifert T, Hervás C, Toledo P. Diseño y validación del cuestionario sobre percepciones y actitudes hacia el aprendizaje por dispositivos móviles (Spanish) [Design and validation of the questionnaire on perceptions and attitudes towards learning for mobile devices]. Pixel-Bit. Revista de Medios y Educación 2019; 54: 45–64.

- Pérez D. eJUNIOR: Sistema de Realidad Aumentada para el conocimiento del medio marino en educación primaria (Spanish) [eJUNIOR: An augmented reality system to know deep sea in primary school]. Quid 2015; 24: 35–42.

- Fonseca D, Redondo E, Valls F. Motivación y mejora académica utilizando realidad aumentada para el estudio de modelos tridimensionales arquitectónicos (Spanish) [Motivation and academic improvement using augmented reality for the study of three-dimensional architectural models]. Education in the Knowledge Society 2016; 17(1): 45–64.

- Bacca J, Baldiris S, Fabregat R, et al. Augmented Reality trends in education: A systematic review of research and applications. Educational Technology y Society 2014; 17(4): 133–149.

- Bressler D, Bodzin A. A mixed methods assessment of students flow experiences during a mobile augmented reality science game. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning 2013; 29(6): 505–517.

- Cabero J, Barroso J, Llorente C. La realidad aumentada en la enseñanza universitaria. REDU. Revista de Docencia Universitaria 2019; 17(1): 105–118.

- Radu I. Augmented reality in education: A metareview and cross-media analysis. Personal and Ubiquitous Computing 2014; 18(6): 1–11.

- Barroso J, Cabero J, Gutiérrez J. La producción de objetos de aprendizaje en realidad aumentada por estudiantes universitarios. Grado de aceptación de esta tecnología y motivación para su uso (Spanish) [The production of objects of learning in augmented reality by university students. Degree of acceptance of such technology and motivation for usage]. Revista Mexicana de Investigación Educativa 2018; 23(79): 1261–128.

- Estapa A, Nadolny L. The effect of an augmented reality enhanced mathematics lesson on student achievement and motivation. Journal of STEM Education 2015; 16(3): 40–48.

- Barroso J, Gallego O. Learning resource production in Augmented Reality supported by education students. Edmetic. Revista de Educación Mediática y TIC 2017; 6(1): 23–38.

- Cabero J, Barroso J, Gallego O. The production of objects of learningin augmented reality by the students. The students as information prosumers. Tecnología Ciencia y Educación 2018; 11: 15–46.

- Del Cerro F, Morales G. Augmented reality as a tool for improving spatial intelligence in secondary education students. RED. Revista de Educación a Distancia 2017; 17(54): 2–14.

- Ibáñez M, Delgado C. Augmented reality for STEM learning: A systematic review. Computers and Education 2018; 123: 109–123.

- Toledo P, Sánchez J. Augmented reality in primary education: Effects on learning. Revista Latinoamericana de Tecnología Educativa 2017; 16(1): 79–92.

- Blas D, Vázquez E, Morales B, et al. Use of augmented reality apps in university classrooms. Campus Virtuales 2019; 8(1): 37–48.

- Cabero J, Barroso J. The educational possibilities of Augmented Reality. New approaches in educational research. 2016; 5(1): 46–52.

- De la Torre J, Martín N, Saorín J, et al. Ubiquitous learning environment with augmented reality and tablets to stimulate comprehension of the tridimentional space. RED, Revista de Educación a Distancia 2013; 37: 2–17.

- Cabero J, Llorente M, Gutiérrez J. Evaluation by and from users: Learning objects with Augmented Reality. RED. Revista de Educación a distancia 2017; 53: 1–17.

- Cabero J, Pérez J. TAM model validation adoption of augmented reality through structural equations. Estudios Sobre Educación 2018; 34: 129–153.

- Sans A. Métodos de investigación de enfoque experimental (Spanish) [Experimental research methods]. In: Rafael B (editor). Metodología de la investigación educative. Madrid: La Muralla; 2004.

- Berardi L. La investigación cuantitativa (Spanish) [Quantitative research]. In: Abero L, Berardi L, Capcasale A, et al. (editors). Investigación educativa. Abriendo puertas al conocimiento. Montevideo: Camus Editores; 2015.

- Matas A. Likert-type scale format design: State of art. Revista Electrónica de Investigación Educativa 2018; 20(1): 38–47.

- Nadler J, Weston R, Voyles E. Stuck in the middle: The use and interpretation of midpoints in items on questionnaires. The Journal of General Psychology 2015; 142(2): 71–89.

- Cabero J, Infante A. Using the delphi method and its use in communication research and education. EDUTEC, Revista Electrónica de Tecnología Educativa 2014; 48: 1–16.

- George C, Trujillo L. Application of the modified delphi method for the validation of a questionnaire on the incorporation of ict in teaching practice. Revista Iberoamericana de Evaluación Educativa 2018; 11(1): 113–134.

- Pedroza L. Development and validation of an instrument for evaluating the teaching practice in early childhood education. Revista Iberoamericana de Evaluación Educativa 2017; 10(1): 109–129.

- De la Horra I. Augmented reality, an educational revolution. EDMETIC, Revista de Educación Mediática y TIC 2017; 6(1): 9–22.

- Plaza de la Hoz J. Benefits and drawbacks of adolescent ICT use: The students’ point of view. Revista Complutense de Educación 2016; 29(2): 491–508.

- Ibáñez M, Di Serio A, Villarán D, et al. Experimenting with electromagnetism using augmented reality: Impact on flow student experience and educational effectiveness. Computers & Education 2014; 71: 1–13.

- Martín J, Fabiani P, Benesova W, et al. Augmented reality to promote collaborative and autonomous learning in higher education. Computers in Human Behavior 2015; 51(2): 752–761.

- Duh H, Klopher E. Augmented reality learning: New learning paradigm in cospace. Computers & Education 2013; 68: 534–535.

- Fernández B. Aplicación del Modelo de Aceptación Tecnológica (TAM) al uso de la realidad aumentada en estudios universitarios de educación primaria (Spanish) [Application of the technological acceptance model (TAM) to the use of augmented reality in university studies of primary education]. In: Roig R (editor). Tecnología, innovación e investigación en los procesos de enseñanza-aprendizaje. Barcelona: Octaedro; 2016.

- Kim K, Hwang J, Zo H. Understanding users’ continuance intention toward smartphone augmented reality applications. Information Development 2016; 32(2): 161–174.

- Garay U, Tejada E, Castaño C. Perceptions of the student to learning through enriched educational objects with augmented reality. Edmetic. Revista de Educación Mediática y TIC 2017; 6(1): 145–164.

- Joo J, Martínez F, Garcia J. Augmented reality and mobile pedestrian navigation with heritage thematic contents: Perception of learning. RIED. Revista Iberoamericana de Educación a Distancia 2017; 20(2): 93–118.

Supporting Agencies

Copyright (c) 2020 Carlos Enrique George Reyes

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This site is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0).

Prof. Zhigeng Pan

Professor, Hangzhou International Innovation Institute (H3I), Beihang University, China

Prof. Jianrong Tan

Academician, Chinese Academy of Engineering, China

Conference Time

December 15-18, 2025

Conference Venue

Hong Kong Convention and Exhibition Center (HKCEC)

...

Metaverse Scientist Forum No.3 was successfully held on April 22, 2025, from 19:00 to 20:30 (Beijing Time)...

We received the Scopus notification on April 19th, confirming that the journal has been successfully indexed by Scopus...

We are pleased to announce that we have updated the requirements for manuscript figures in the submission guidelines. Manuscripts submitted after April 15, 2025 are required to strictly adhere to the change. These updates are aimed at ensuring the highest quality of visual content in our publications and enhancing the overall readability and impact of your research. For more details, please find it in sumissions...

.jpg)

.jpg)