Asia Pacific Academy of Science Pte. Ltd. (APACSCI) specializes in international journal publishing. APACSCI adopts the open access publishing model and provides an important communication bridge for academic groups whose interest fields include engineering, technology, medicine, computer, mathematics, agriculture and forestry, and environment.

Flexibility in augmented reality storytelling apps

Vol 1, Issue 2, 2020

Download PDF

Abstract

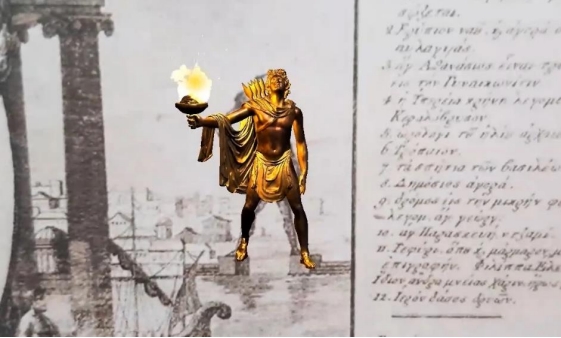

This research inquiries about the flexibility of two augmented reality storytelling apps, as well as eight specific variables of this cognitive characteristic of creativity from the Creapp 6–12 questionnaire. The study concludes that they meet all the specific variables of flexibility, used in convergent and divergent mode activities: they stimulate critical and divergent thinking, accessibility and adaptation to different levels of difficulty, including variety of codes, allow the interrelation of disparate elements, build different stories, manipulate and exchange elements, change and reformulate the story.

Keywords

References

- Scolari CA, Masanet MJ, Guerrero-Pico M, et al. Transmedia literacy in the new media ecology: Teens’ transmedia skills and informal learning strategies. El Profesional de la Información 2018; 27(4): 801–812.

- Martinez Rodrigo E, Sánchez Martin L. Publicidad en internet: Nuevas vinculaciones en las redes sociales (Spanish) [Internet advertising: New links in social networks]. Vivat Academia 2011; 117: 469–480.

- Maldonado Rivera CA. Narrativa hipertextual mapuche: Emplazamiento y reivindicación cultural en Youtube (Spanish) [Mapuche hypertextual narrative: Cultural Emplacement and claiming on Youtube]. Revista de Comunicación de la SEECI 2011; 26: 62–70.

- Cantillo Valero C. The story to film animation: semiology of digital storytelling. Revista de Comunicación de la SEECI 2015; 38: 115–140.

- Herrero de la Fuente M, García Domínguez A. Facebook Live and social television: The use of streaming in Antena 3 and laSexta. Vivat Academia 2019; 146: 43–70.

- Acosta Véliz M, Jiménez Cercado M. Importancia de la oferta académica de las principales plataformas MOOC (Massive Open Online Course) para las ciencias administrativas (Spanish) [Importance of the academic offerings of the main MOOC (Massive Open Online Course) platforms for administrative sciences]. Vivat Academia 2018; 145: 97–111.

- Ivanov Ivanov S. Old town of heraclea sintica. Archaeological heritage adaptation in southwest of Bulgaria. Inclusions Magazine 2020; 7(2): 437–444.

- Campillo-Alhama C, Martínez-Sala AM. Events 2.0 in the transmedia branding strategy of World Cultural Heritage Sites. El profesional de la Información 2019; 28(5): e280509.

- Felipe Morales A, Barrios E, Caldevilla Domínguez D. Políticas de gmento de la lectura a través del futuro profesorado (Spanish) [Policies for the promotion of reading through future teachers]. Utopia y praxis Latinoamericana 2019; 24(4): 89–103.

- García Marín D. Universo transpodcast. Modelos narrativos y comunidad independiente (Spanish) [Transpodcast universe. Narrative models and independent community]. Historia y Comunicación Social 2020; 25(1): 139–150.

- Trucco D, Palma A. Infancia y adolescencia en la era digital: Un informe comparativo de los estudios de Kids Online del Brasil, Chile, Costa Rica y el Uruguay (Spanish) [Childhood and adolescence in the digital age: A comparative report of kids online studies from Brazil, Chile, Costa Rica and Uruguay] [Internet]. 2020. Available from: https://www.cepal.org/es/publicaciones/45212-infancia-adolescencia-la-era-digital-un-informe-comparativo-estudios-kids-online.

- Manas Valle S, Pena Timón V. Relatos derivados: Un viaje aumentado por la urbe (Spanish) [Derivative stories: An augmented journey through the city]. Opción 2016; 32(7): 1047–1067.

- Martínez-Cano FJ, Ivars-Nicolás B, Martínez-Sala AM. Ubicuidad dual: Base para laefectividad del vrcinema como herramienta prosocial. Análisis de hunger in L.A. y after solitary (Spanish) [Dual ubiquity: basis for the effectiveness of vrcinema as a prosocial tool. Analysis of hunger in L.A. and after solitary]. Perspectivas de la Comunicación 2020; 13(1): 155–176.

- Carrera Álvarez P, Limón Serrano N, Herrero Curiel E, et al. Transmedialidad y ecosistema digital (Spanish) [Transmediality and digital ecosystem]. Historia y Comunicación Social 2014; 18: 535–545.

- Reinoso R. Posibilidades de la RA en educación (Spanish) [Possibilities of AR in education]. In: Hernández J, Penessi M, Sobrino D, et al. (editors). Tendencias emergentes en educación con TIC. Barcelona: Espiral; 2012. p. 175–196.

- Cabero Almenara J, Barroso Osuna J. Ecosistema de aprendizaje con RA: Posibilidades educativas (Spanish) [Learning ecosystem with AR: Educational possibilities]. Tecnologia, Ciencia y Educación 2016; 5: 141–154.

- Roig-Vila RS, Lorenzo Lledó A, Mengual Andrés S. Utilidad percibida de la RA como recurso didáctico en educación infantil (Spanish) [Perceived usefulness of AR as a didactic resource in early childhood education]. Red Universitaria de Campus Virtuales (RUCV) 2019; 8(1): 19–35.

- López Meneses E, Vázquez Cano E, Gómez Galán J, et al. Pedagogía de la innovación con tecnologías. Un estudio de caso de la Universidad Pablo Olavide (Spanish) [Pedagogy of innovation with technologies. A case study of the Pablo Olavide University]. El Guiniguada 2019; 28: 76–92.

- Colussi J, Assunção Reis T. Periodismo inmersivo. Análisis de la narrativa en aplicaciones de realidad virtual (Spanish) [Immersive journalism. Analysis of narrative in virtual reality applications]. Revista Latina de Comunicação Social 2020; 77: 19–32.

- Paíno-Ambrosio A, Rodríguez-fidalgo MI. Propuesta de “géneros periodísticos inmersivos” basados en la realidad virtual y el vídeo en 360º (Spanish) [Proposal of “immersive journalistic genres” based on virtual reality and 360º video.]. Revista Latina de Comunicación Social 2019; 74; 1132–1153.

- Rodríguez Fidalgo MI, Molpereces Arnáiz S. The inside experience y la construcción de la narrativa transmedia. Un análisis comunicativo y teóricoliterario (Spanish) [The inside experience and the construction of the transmedia narrative. A communicative and literary-theoretical analysis]. Cuadernos de Información y Comunicación 2014; 19: 315–330.

- Peña Acuña B. Innovación en el uso del formato narrativo digital de AR aplicado a la didáctica de la lengua y la literatura en educación primaria (Spanish) [Innovation in the use of the AR digital narrative format applied to the teaching of language and literature in primary education]. Recio Jiménez R, Ajejas Bazán J, Durán Medina JF (editors). Nuevas técnicas docentes. Madrid: Pirámide (Anaya); 2019.

- Peña Acuña B. Innovación aplicada a la didáctica de la lengua y la literatura (Spanish) [Innovation applied to the teaching of language and literature]. Madrid: ACCI; 2019.

- Magadán C. Palabras aumentadas: Jugar para reflexionar sobre la lengua. Textos. Didáctica de la Lengua y la literature (Spanish) [Augmented words: Playing to reflect on the language. Texts. Didactics of language and literature.]. Nuevas Estrategias Didácticas 2019; 85: 20–28.

- Darici K. Comics and transmedia: François Schuiten’s Atlantic 12 in Enhanced Reality. Cuadernos de Información y Comunicación 2014; (19): 303–313.

- Framinán de Miguel MJ. Usos de la narrativa breve como práctica colaborativa y experiencia intercultural (Spanish) [Uses of short narrative as collaborative practice and intercultural experience]. Opción 2015; 31(4): 441– 450.

- Gallego Pérez OM. Estudio y análisis sobre las posibilidades educativas de la RA como herramienta de producción de experiencias formativas por parte del alumnado universitario (Spanish) [Study and analysis on the educational possibilities of AR as a tool for the production of formative experiences by university students] [PhD thesis]. Spain: University of Córdoba; 2018.

- Urbano Cayuela R. Creación de marcas infantiles de Animación transmedia y multipantallas: “Piny, Institute of New York”, y “Cleo & Luquin”/”Familia Telerin” (Spanish) [Creation of children’s brands of transmedia and multiscreen Animation: Piny, Institute of New York”, and “Cleo & Luquin7’’ “Telerin Family”] [PhD thesis]. Spain: University of Huelva; 2019.

- Mari Martí F. Una educació literária transmèdia. Reptes y possibilitats de la formació lectora i literária més enllà del paper (Spanish) [A transmedia literary education. Challenges and possibilities of reading and literary education beyond the paper] [PhD thesis]. Spain: University of Valencia; 2019.

- Fombella Coto I, Arias Blanco JM, San Pedro Veledo JC. Arquitectura escolar ymetodologías docentes en el siglo XXI: Respuestas a un nuevo paradigma educativo (Spanish) [School architecture and teaching methodologies in the 21st century: Responses to a new educational paradigm. Revista in Clusiones 2019; 6(4): 64–91.

- Guilford JP. Creatividad y educación (Spanish) [Creativity and education]. Buenos Aires: Paidós; 1978.

- Peña Acuña B. Creatividad verbal. Barcelona: Octaedro; 2020.

- European Commission. Recommendation of the European Parliament and of the Council of 18 December 2006 on key competences for lifelong learning (2006/962/EC) [Internet]. Official Journal of the European Union; 2006. Available from: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?Uri=celex %3A32006H0962.

- Del Moral Pérez ME, Bellver C, Guzmán Duque AP. Evaluación de la potencialidad creativa de aplicaciones móviles creadoras de relatos digitales para Educación Primaria (Spanish) [Evaluating the creative potential of digital storytelling APPs for primary education]. Ocnos: Revista De Estudios Sobre Lectura 2019; 18(1): 7–20.

- Kharkhurin A. The big question in creativity research: The transcendental source of creativity. Creativity. Neories-Research-Applications 2015; 2(1): 90–96.

- Romo M, Alfonso V, Sanchez M. El test de creatividad infantil (TCI): Evaluando la creatividad mediante una tarea de encontrar problemas (Spanish) [The child creativity test (TCI): Assessing creativity through a problem finding task]. Psicología Educativa 2016; 22(2): 93–101.

- Rodríguez-Martínez C, Díez E. Conocimiento y competencias básicas en la formación inicial de maestras y maestros (Spanish) [Knowledge and basic competencies in the initial training of teachers]. Profesorado, Revista de Currículum y Formación del Profesorado 2014; 18(1): 383–396.

- Del Moral Pérez ME, Bellver MC, Guzmán AP. CREAPP K6-12: Instrumento para evaluarla potencialidad creativa de app orientadas al diseño de relatos digitales personales (Spanish) [CREAPP K6-12: Instrument to evaluate the creative potential of apps oriented to the design of personal digital stories]. Digital Education Review 2018; 33: 284–305.

- Leinonen T, Keune A, Veermans M, et al. Mobile apps for reflection in learning: A design research in K-12 education. British Journal of Educational Technology 2016; 5(2): 184–202.

- Sanz Pilar N, García Rodríguez A. Los desarrolladores de libros apps. infantiles y juveniles: Características, perspectivas y modelo de negocio (Spanish) [Application developers and app books for children and young people in Spain: Characteristics, prospects and business model]. Anales de Documentación 2014; 17(2): 1–18.

- Sánchez Fuentes S, Martín Almaraz RA. Formación docente para atender a la diversidad. Una experiencia basada en las TIC y el diseño universal para el aprendizaje (Spanish) [Teachers training to deal to diversity. An experience based on ICT and universal design for learning]. Revista de Ciencias de la Comunicación e Información 2016; 21(2): 35–44.

- Gairín Sallán J, Mercader C. Usos y abusos de las TIC en los adolescentes (Spanish) [Uses and abuses of ICT in adolescents]. Revista de Investigación Educativa 2018; 36(1): 125–140.

- Cabero Almenara J, Barroso Osuna J. ICT teacher training: A view of the TPACK Model. Cultura y Educación 2016b; 28(3): 633–663.

- Sánchez Marín FJ, López Mondéjar LM. La relación educativa desde la perspectiva ética del desempeño docente (Spanish) [Educational relation from the teacher performance ethics perspective]. Revista de Ciencias de la Comunicación e Información 2016; 21(2): 45–65.

- Catalina-García B, López De Ayala-López MC, Martínez Pastor E. Usoscomunicativos de las nuevas tecnologías entre los menores. Percepción de sus profesores sobre oportunidades y riesgos digitales (Spanish) [Communicative uses of new technologies among minors. Teachers’ perception about digital opportunities and risks]. Mediaciones Sociales 2019; 18: 43–57.

- Fernández Robles B. Factores que influyen en el uso y aceptación de objetos de aprendizaje de RA en estudios universitarios de educación primaria (Spanish) [Factors that influence the use and acceptance of learning objects of augmented reality in university studies of primary education]. Edmetic, Revista de Educación Mediática y TIC 2017; 6(1): 203–220.

- Martínez-Sala AM, Alemany D, Segarra-Saavedra J. Las TIC como origeny solución del plagio académico. Análisis de su integración como herramienta de aprendizaje (Spanish) [ICT as a source of and solution to academic plagiarism. Analysis of their integration as a learning tool]. In: Roig-Vila R (editor). Investigación e innovación en la Enseñanza Superior. Nuevos contextos, nuevas ideas. Barcelona: Ediciones Octaedro; 2019. p. 1208–1218.

- Alderete V, Di Meglio G, Formichella M. Acceso a lasTIC y rendimiento educativo:¿Una relación potenciada por su uso? Un análisis para España (Spanish) [ICT access and educational performance: A relationship enhanced by ICT use? An analysis for Spain]. Revista de Educacion 2017; 377: 54–81.

- Ariza MR, Quesada A. Nuevas tecnologías y aprendizaje significativo de las ciencias (Spanish) [New technologies and meaningful science and meaningful learning]. Enseñanza de las ciencias 2014; 32(1): 101–115.

- Manas Pérez A, Roig-Vila R. Las Tecnologías de la Información y la Comunicación en el ámbito educativo. Un tándem necesario en el contexto de la sociedad actual (Spanish) [Information and Communication Technologies in education. A necessary tandem in the context of today’s society]. Revista Internacional d’Humanitats 2019; 45: 75–86.

- Mermoud SR, Ordonez C, García Romano L. Potentialities of a virtual learning environment for argumentation in high school science classes. Eureka Journal on Science Education and Outreach 2017; 14(3): 587–600.

- Cabero Almenara J, Vázquez-Cano E, López Meneses E, et al. Potencialidades de un entorno virtual de aprendizaje para argumentar en clases de ciencias en la escuela secundaria (Spanish) [Potentialities of a virtual learning environment to support students’ argumentation in science classes at secondary school]. Revista Complutense de Educación 2020; 31(2): 141–152.

- Bacca J, Baldiris S, Fabregat R, et al. Augmented reality trends ineducation: A systematic review of research and applications. Journal of Educational Technology & Society 2014; 17(4): 133–149.

- Dunleavy M, Dede C, Mitchell R. Affordances and limitations of immersive participatory augmented reality simulations for teaching and learning. Journal of Science Education and Technology 2009; 18(1): 7–22.

- Prendes C. RA y educación: Análisis de experiencias practices (Spanish) [AR and education: Analysis of practices]. Píxel-Bit. Revista de Medios y Educación 2015; 46: 187–203.

- Villalustre L, Del Moral ME, Neira-Pineiro MR. Percepción docente sobre la RA en la enseñanza de Ciencias en Primaria. Análisis DAFO (Spanish) [Teachers’ perception about augmented reality for teaching science in primary education. SWOT Analysis]. Revista Eureka sobre Enseñanza y Divulgación de las Ciencias 2019; 16(3): 3201.

- Barroso Osuna J, Cabero Almenara J, Moreno-Fernández AM. La utilización deobjetos de aprendizaje en RA en la enseñanza de la medicina (Spanish) [The use of learning objects in augmented reality in the teaching of medicine]. International Journal of Technology and Educational Innovation 2016; 2(2): 77–83.

- Flores-Bascuñana M, Diago PD, Villena-Taranilla R, et al. On augmented reality for the learning of 3d-geometric contents: A preliminary Exploratory study with 6-grade primary students. Education Sciences 2020; 10(1): 4.

- Fracchia CC, Alonso De Armino AC, Martins A. RA aplicada a la enseñanza de Ciencias Naturales (Spanish) [Augmented reality applied to natural science teaching]. Revista Iberoamericana de Tecnología en Educación y Educación en Tecnología, TE & ET 2015; 16: 7–15.

- Fracchia C, Martins A. Realidad aumentada en la enseñanza primaria: Diseño de juegos de mesa para las áreas ciencias sociales y matemáticas (Spanish) [Augmented reality in the primary education: Design of table games for the social sciences and mathematics area]. Revista Electrónica de Investigación, Docencia y Creatividad 2018; 6: 89–104.

- Toledo Morales P, Sánchez García JM. RA en Educación Primaria: Efectos sobre el aprendizaje (Spanish) [Augmented Reality in Primary Education: Effects on learning]. Revista Latinoamericana de Tecnología Educativa 2017; 16(1): 79–92.

- De La Horra Villacé GI. RA, una revolución educativa (Spanish) [Augmented reality, an educational revolution]. Edmetic, Revista de Educación Mediática y TIC 2017; 6(1): 9–22.

- Rivadulla López JC, Rodríguez Correa M. La incorporación de la RA en las clases de ciencias (Spanish) [Incorporation of augmented reality in sciences classroom]. Contextos Educativos 2020; 25: 237–255.

- Fombona J, Pascual MÁ. La producción científica sobre RA, un análisis de la situación educativa desde la perspectiva SCOPUS (Spanish) [The scientific production on AR, an educational literature review in SCOPUS]. Edmetic, Revista de Educación Mediática y TIC 2017; 6(1): 39–61.

- Sáez-López JM, Sevillano-García ML, Pascual-sevillano MA. Aplicación deljuego ubicuo con RA en Educación Primaria (Spanish) [Application of the ubiquitous game with augmented reality in Primary Education]. Comunicar: Revista Científica de Comunicación y Educación 2019; 27(61): 71–82.

- Knaus T. Padagogik des digitale: Phanomene, potentiale, perspektiven (German) [Pedagogy of the digital: Phenomena, potentials, perspectives]. In: Eder S, Mikat C, Tillmann A (editors). Software takes command. Munchen: Kopaed; 2017. p. 40–68.

- Martínez-Sala AM, Alemany Martínez D. Integración eficiente de redes sociales como herramientas complementarias de aprendizaje y para la alfabetización digital en los estudios superiores de Publicidad y RR. PP (Spanish) [Efficient integration of social networks as complementary learning tools and for digital literacy in higher studies in Advertising and PR]. In: Roig-Vila R (Editor). El compromiso académico y social a través de la investigación e innovación educativas en la Enseñanza Superior. Barcelona: Ediciones Octaedro; 2018. p. 1126–1136.

- Cabero Almenara J, Barroso Osuna J. The educational possibilities of Augmented Reality. New Approaches in Educational Research 2016; 5(1): 46–52.

- Lorenzo G, Scagliarini C. Revisión bibliométrica sobre la RA en educación (Spanish) [Bibliometric review of augmented reality in education]. Revista General de Información y Documentación 2018; 28(1): 45–60.

- Passey D, Shonfeld M, Appleby L, et al. Digital agency: Empowering equity in and through education. Technology, Knowledge and Learning 2018; 23(3): 425–439.

- Billinghurst M, Dunser A. Augmented reality in the classroom. Computer 2012; 45(7): 56–63.

- Cabero Almenara J, Barroso Osuna J. RA: Posibilidades educativas (Spanish) [AR: Educational possibilities]. In: Ruiz J, Sánchez J, Sánchez E (editors). Innovaciones con tecnologías emergentes. Málaga: University of Málaga; 2015. p. 1–15.

- Cózar R, De Moya M, Hernández J, et al. Emerging technologies in social sciences teaching. An experience using augmented reality in teacher training. Digital Education Review 2015; 27: 138–153.

- Cabero Almenara J, Marín-Díaz V. Blended learning and augmented reality: Experiences of educational design. RIED, Revista Iberoamericana de Educación a Distancia 2018; 21(1): 57–74.

- Scott G, Leritz L, Mumford M. The effectiveness of creativity training: A quantitative review. Creativity Research Journal 2004; 16(4): 361–388.

- Guilford J. La naturaleza de la inteligencia humana (Spanish) [The nature of human intelligence]. Buenos Aires: Paidós; 1977.

- Torrance EP. Tests of creative linking. Lexington, MA: Personnel Press; 1966.

- Salmerón L, Delgado P. Critical analysis of the effects of the digital technologies on reading and learning. Cultura y Educación 2019; 31(3): 465–480.

Supporting Agencies

Copyright (c) 2020 Beatriz Peña-Acuña, Alba-María Martínez-Sala, Andrea Felipe Morales

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This site is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0).

Prof. Zhigeng Pan

Professor, Hangzhou International Innovation Institute (H3I), Beihang University, China

Prof. Jianrong Tan

Academician, Chinese Academy of Engineering, China

Conference Time

December 15-18, 2025

Conference Venue

Hong Kong Convention and Exhibition Center (HKCEC)

...

Metaverse Scientist Forum No.3 was successfully held on April 22, 2025, from 19:00 to 20:30 (Beijing Time)...

We received the Scopus notification on April 19th, confirming that the journal has been successfully indexed by Scopus...

We are pleased to announce that we have updated the requirements for manuscript figures in the submission guidelines. Manuscripts submitted after April 15, 2025 are required to strictly adhere to the change. These updates are aimed at ensuring the highest quality of visual content in our publications and enhancing the overall readability and impact of your research. For more details, please find it in sumissions...

.jpg)

.jpg)