Changes in green area of two city halls in Mexico City from 1990 to 2015

Vol 2, Issue 2, 2021

Download PDF

Abstract

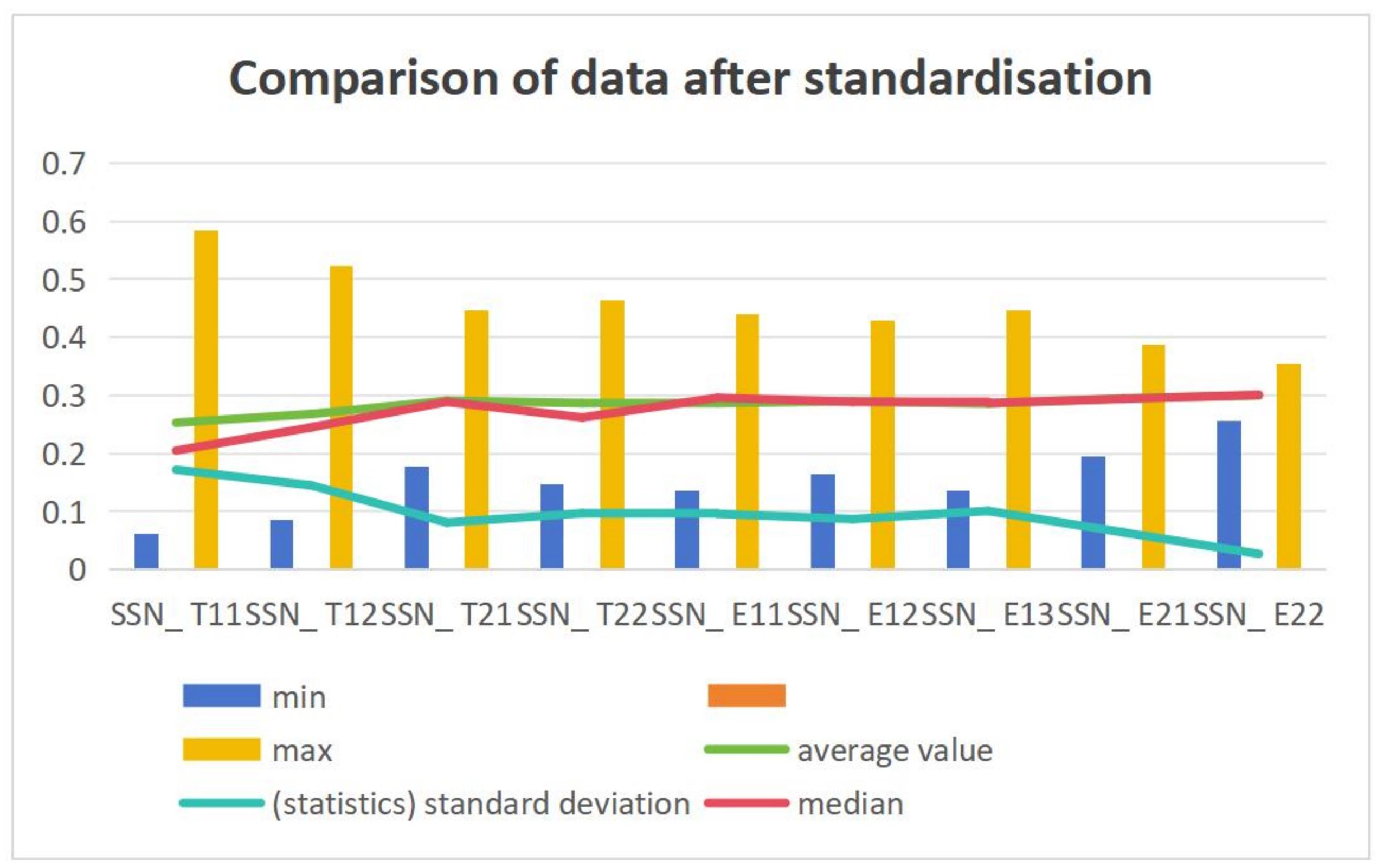

Urban green spaces play a crucial role in urban sustainability because they provide a variety of environmental and social benefits, which is why every city claiming to be modern, safe, inclusive, and sustainable must ensure that its residents have access to and use these spaces. Mexico City has been upgraded to a city in transition to sustainable development, which is why it has launched various plans and actions focusing on environmental protection. Therefore, the main purpose of this study is to compare the AVU area of the two urban centers of the city from 1990 to 2015 using the census of the Geographic Information System (GIS) and the National Institute of Statistics and Geography. Information is used to understand the social situation of each mayor’s office during the study period. The results show that although the social gap has narrowed in this period, there are great differences in area and quality between the two cities.

Keywords

References

- ONUHabitat. Índice básico de las ciudades prosperas: Miguel Hidalgo (Spanish) [Prosperous cities core index: Miguel Hidalgo]. Ciudad de México: ONUHabitat; 2016.

- Secretaría del Medio Ambiente. Inventario de áreas verdes del Distrito Federal (SEDEMA) (Spanish) [Inventory of green areas in the Federal District (SEDEMA)]. Ciudad de México: Secretaría del Medio Ambiente; 2003.

- Sierra Rodríguez I, Ramírez-Silva JP. Los parques como elementos de sustentabilidad de las ciudades (Spanish) [Parks as elements of sustainability in cities]. Revista Fuente 2010; 2(5): 6–14.

- Gómez Gutiérrez C. El desarrollo sostenible: Conceptos básicos, alcances y criterios para su evaluación (Spanish) [Sustainable development: Basic concepts, achievements and criteria for assessment]. In: Cambio Climático y Desarrollo Sostenible: Bases conceptuales para la educación en Cuba (Educación). La Habana: Editorial Educación Cubana; 2014.

- López E. Beneficios en la implementación de áreas verdes urbanas para el desarrollo de ciudades turísticas (Spanish) [Benefits in the implementation of urban green areas for the development of tourist cities]. Topofilia: Revista de Arquitectura, Urbanismo y Ciencias Sociales 2013; 4(1): 16.

- Salvador Palomo PJ. La planificación verde en las Ciudades (Spanish) [Green planning in cities]. Madrid: Gustavo Gili; 2003.

- Kendal D, Lee K, Ramalho C, et al. Benefits of urban green space in the Australian context. Melbourn: Clean Air and Urban Landscape NESP Hub; 2016.

- Observatorio de Medio Ambiente Urbano. Agenda 21 Málaga 2015: Agenda urbana en la estrategia de sostenibilidad integrada 2020–2050 (Spanish) [Agenda 21 Malaga 2015: Urban Agenda in the integrated sustainability strategy 2020–2050]. Malaga: Málaga City Council; 2015

- Sherer PM. The benefits of parks: Why America needs more city parks and open space. San Francisco, California: The Trust for Public Land 2003; 32.

- Flores-Xolocotzi R. Incorporando desarrollo sustentable y gobernanza a la gestión y planificación de áreas verdes (Spanish) [Incorporating sustainable development and governance to the management and planning of urban green areas]. Frontera Norte 2012; 24(48): 165–190.

- Reyes Päcke S, Figueroa Aldunce IM. Distribution, surface area and accessibility of green areas in Santiago de Chile. EURE 2010; 36(109): 89–110.

- Procuraduria Ambiental y de Ordenamiento Territorial. Presente y Futuro de las Áreas Verdes y del Arbolado de la Ciudad de México (Ekilibria) (Spanish) [The present and future of Mexico City’s green areas and the Arbo-side of Mexico City (Ekilibria)]. Ciudad de México: Estudios y Publicaciones; 2010.

- Hinojosa Robles E. Urban green infrastructure management in Mexico City and Beijing: The search for sustainable cities. Investigación Ambiental 2014; 6(1): 69–77

- Galindo-Bianconi AS, Victoria-Uribe R. La vegetación como parte de la sustentabilidad urbana: beneficios, problemáticas y soluciones para el Valle de Toluca (Spanish) [Vegetation as part of urban sustainability: Benefits, problems and solutions for the Toluca Valley]. Quivera 2012; 14(1): 98–108.

- Pérez-Medina S, López-Falfán I. Green spaces and urban trees in Merida, Yucatan. Toward urban sustainability. Economía, Sociedad y Territorio 2015; 15(47): 1–33.

- Bolin B, Matranga E, Hackett EJ, et al. Environmental equity in a sunbelt city: The spatial distribution of toxic hazards in Phoenix, Arizana. Global Environmental Change Part B: Environmental Hazards 2000; 2(1): 11–24.

- Benítez G, Chacalo A, Barois I. Aportes A La Ecologia Urbana De La Ciudad De Mexico (Spanish) [Contributions to the urban ecology of Mexico City]. In: Rapoport EH, López-Moreno IR (editors), Aportes a la Ecología Urbana de la Ciudad de México. Ciudad de México: Limusa; 1987. p. 193–201.

- Flores-Xolocotzi R, Gonzáles-Guillen MJ. Green areas and public park planning. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Forestales 2010; 1(1): 17–24.

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística Geografía e Informática. Anuario estadístico y geográfico del Distrito Federal 2015 (INEGI). Ciudad de México: INEGI; 2015.

- Bolivar Espinoza GA, Caloca Osorio OR. Distribución espacial de la pobreza (Spanish) [Spatial distribution of poverty]. Distrito Federal de México 1990–2040. Polis: Revista Latinoamericana 2011; (29): 1–29

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística Geografía e Informática. Producto interno bruto por entidad federativa 1997–2002 (INEGI) (Spanish) [Gross domestic product by state 1997–2002 (INEGI)]. Ciudad de México: INEGI; 2020.

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística Geografía e Informática. Banco de Información Eonómica (Spanish) [Eonomic Information Bank] [Internet]. 2017 [updated 2017 Apr 26]. Available from: https://www. inegi.org.mx/sistemas/bie/?idserPadre=10200070#D10200070

- National Social Development Policy Evaluation Committee. Poverty reporting and assessment. Mexico City: NSDPEC; 2013.

- Secretaría del Medio Ambiente. Agenda ambiental de la ciudad de México programa de Medio Ambiente 2007–2012 (Spanish) [Mexico urban environmental agenda, environmental programme 2007–2012]. Ciudad de México: Sedema; 2012.

- AlMomento.mx. Presentan denuncia popular por impacto ambiental en obra de Mixcoac (Spanish) [Popular complaint filed for environmental impact of Mexico construction project] [Internet]. 2017 [updated 2017 Jul 9]. Available from: https://almom ento.mx/presentan-denuncia-popular-por-impacto-ambiental-en-obra-de-mixcoac/.

- Ancira-sánchez L, Trevinho Garza EJ. Using satellite images for forest management in northeast Mexico. Madera y Bosques 2015; 21(1): 77–91.

- Vera R. Mexico Tren México-Toluca: Ecocidio, descontento social y los mismos socios del poder (Spanish) [Toluca train: Ecological killing, social discontent and the same power partners from the process] [Internet]. 2017 [updated 2017 Jul 13]. Available from: https://www.proceso.com.mx/3918 95/tren-mexico-toluca-ecocidio-descontento-social-y-los-mismos-socios-del-poder-2.

- Aguilar N, Galindo G, Fortanelli J, et al. Índice normalizado de vegetación en caña de azúcar en la Huasteca Potosina (Spanish) [Normalized index of sugarcane vegetation in the Huasteca Potosina]. Avances En Investigación Agropecuaria 2010; 14(2): 49–65.

- Gonzalez-Elizodo S, Gonzalez-Elizodo M, Cortes-Ortiz A. Vegetación de la Reserva de la Biosfera “La Michila”, Durango, México (Spanish) [Vegetation in the “La Michila” biosphere reserve in Durango, Mexico]. Acta Botánica Mexicana 1993; 22: 1–104.

- Guzman A, López-García J, Manzo Delgado LL. Spectral and visual analysis of vegetation and land use with Landsat ETM+ images assested by digital aerial photography, of the Chichinautzin Biological Corridor, Morelos, Mexico. Investigaciones Geográficas, Boletin Del Instituo de Geografía, UNAM 2008; 1(67): 59–75.

- Trucíos-Caciano R, Estrada-Ávalos J, Cerano-Paredes J, et al. Interpretation of change in land and soil use. Terra Latinoamericana 2011; 29(4): 359–367.

- Aguilar Arias H, Mora Zamora R, Vargas Bolanos C. Metodología para la corrección atmosférica de imágenes Aster, RapidEye, Spot 2 y Landsat 8 con el módulo Flaash del Software ENVI (Spanish) [The method of atmospheric correction for aster, Rapideye, spot 2 and Landsat 8 images by using ENVI software Flaash module]. Revista Geográfica de América Central, Julio-dici 2014; (53): 39–59.

- Sánchez M. El df pierde en 15 Años 56 mil árboles por obras (Spanish) [Mexico City loses 56,000 trees in 15 years due to construction work] [Internet]. 2017 [updated 2017 Jun 13]. Available from: http://www.sinembargo.mx/24-05-2015/1353514.

- Peña Araya MA. Correcciones de una imagen satelital ASTER para estimar parámetros vegetacionales en la cuenca del río Mirta, Aisén (Spanish) [Corrections of an ASTER satellite image to estimate vegetational parameters in the Mirta river basin, Aisén]. Bosque 2007; 28(2): 162–172.

- Meneses-Tovar CL. El índice normalizado diferencial de la vegetación como indicador de la degradación del bosque (Spanish) [The normalized differential vegetation index as an indicator of forest degradation]. Revista Internacional de Silvicultura e Industrias Forestañes 2011; 62(238): 72.

- Soria Ruiz J, Granados Ramirez R. Obtenidos de los sensores AVHRR del satélite NOAA y TM del Landsat (Spanish) [Relationship between vegetation indices obtained from NOAA satellite AVHRR and Landsat TM sensors]. Ciencia Ergo Sum 2005; 12(2): 167–174.

- Aldana D, Anges T, Bosques Sendra J. Cartography of the land cover/land use of the National Park Sierrade La Culata, Mérida State-Venezuela. Revista Geográfica Venezolana 2008; 49(2): 173–200.

- Hernández F, Maríadela L, Palacios Romero A, et al. Influencia de la urbanización en el cambio de la vegetación colindante del corredor Pachuca-Tizayuca (2000–2014) (Spanish) [Impact of urbanization on vegetation change near Pachuca tizayuca corridor (2000–2014)]. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Forestales 2016; 7(33): 20–39.

- Ramos-Reyes R, Palma-López D, Ortiz Solorio CA, et al. Change of land use by means of geographical information systems in a Cacao region. Terra Latinoamericana 2004; 22(3): 267–278.

- Secretaría de Desarrollo Urbano y Vivienda. Programa Delegacional de Desarrollo Urbano de Miguel Hidalgo (Spanish) [Miguel Hidalgo delegation urban development program]. Mexico: Gaceta Oficial Del Distrito Federal; 2008. p. 169.

- Rivera N. En la casa de la Sal: Monografia, cronicas y leyendas de Iztacalco (Gobierno d) (Spanish) [Salt house: Monographs, chronicles and legends of Iztakarko]. Mexico: Gobierno del Distrito Federal; 2002.

- Secretaría de Desarrollo Urbano y Vivienda. Programa delegacional de desarrollo urbano para la delegación iztacalco (Spanish) [Iztakalko delegation urban development mission program]. Mexico: Gobierno del Distrito Federal; 2008. p. 136.

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística Geografía e Informática. Principales resultados de la encuesta intercensal 2015 (Primera) (Spanish) [Main results of the 2015 intercountry survey]. Aguascalientes: INEGI; 2015.

- Sorensen M, Barzetti V, Williams J. Manejo de las áreas verdes urbanas (Spanish) [Urban green space management]. Washington D.C.: Banco Interamericano de Desarrollo; 1998.

- Handley J. Accessible natural green space. Standards in towns and cities: A review and toolkit for their impementation. Peterborough: Natural England; 2003.

- Atiqul HSM. Urban green spaces and an integrative approach to sustainable environment. Journal of Environmental Protection 2011; 7(2): 601–608.

- Jennings V, Larsen L, Yun J. Advancing sustainability through urban green space: Cultural ecosystem services, equity, and social determinants of health. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2016; 13(196): 15.

- Maas J, Van Dillen S, Vertheij R, et al. Social contact as a possible mechanism behind the relationship between green space and health. Health and Place 2009; 15(2): 586–595.

- World Health Organization. Urban green space and health: A review of evidence [Internet]. Copenhagen: WHO; 2016. Available from: https://www.euro.who. int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0005/321971/Urban-green-spaces-and-health-review-evidence.pdf.

- Fan Y, Das K, Chen Q. Neighborhood green, social support, physical activity, and stress: Assessing the cumulative impact. Health and Place 2011; 17(6): 571–582.

- Grant L. Multifunctional urban green infrastructure. London, UK: CIWEM; 2010.

- Secretaría de Desarrollo Social. Pobreza, Desigualdad y Marginación en la Ciudad de México (Dirección) (Spanish) [Poverty, inequality and marginalization in Mexico City (direction)] [Internet]. Ciudad de México; 2004. Available from: http://www.sideso. cdmx.gob.mx/documentos/2003_seminario_pobreza_y_desigualdad.pdf.

- Asamblea Legislativa del Distrito Federal VI Legislatura. Ley de salvaguarda del patrimonio urbanístico arquitectónico del distrito federal (Spanish) [Law for the safeguarding of the urban architectural heritage of the federal district]; 2014 Nov 28 (Mexico). Available from: http://aldf.gob.mx/archivo-3b5 d31bc1dbb20329e76ef5fa2ec73f6.pdf.

- Urban Green Space Website [Internet]. Berlin: Senate Department for the Environment, Transport and Climate Protection. 2019. Available from: https://w ww.berlin.de/senuvk/natur_gruen/index_en.shtml.

- Cvejić R, Eler K, Pintar M, et al. A typology of urban green spaces, ecosystem services provisioning services and demands [Internet]. 2015 May 13. Available from: https://assets.centralparknyc.org/pdfs/inst itute/p2p-upelp/1.004_Greensurge_A+Typology+of +Urban+Green+Spaces.pdf/.

- Departamento de Ordenación del Territorio y Medio Ambiente. Criterios de sostenibilidad aplicables al planeamiento urbano (Spanish) [Sustainability criteria applicable to urban planning]. 2003 May 22. Available from: https://tysmagazine.com/criterios- sostenibilidad-aplicables-al-planeamiento-urbano/.

- Administración Pública Del Distrito Federal. Decreto de presupuesto de egresos del distrito federal para el ejercicio fiscal 2000 (Spanish) [Federal district expenditure budget decree for fiscal year 2000]. Ciudad de México: Gaceta Oficial del Distrito Federal; 1999. p. 75–79.

- Administración Pública Del Distrito Federal. Decreto de presupuesto de egresos del distrito federal para el ejercicio fiscal 2010 (Spanish) [Decree of expenditure budget of the federal district for fiscal year 2010]. Ciudad de México: Gaceta Oficial del Distrito Federal; 2009. p. 3–31.

- Administración Pública Del Distrito Federal. Decreto de presupuesto de egresos del distrito federal para el ejercicio fiscal 2015 (Spanish) [Decree of expenditure budget of the federal district for fiscal year 2015]. Ciudad de Méxio: Gaceta Oficial del Distrito Federal; 2014. p. 19–23.

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística Geografía e Informática. Los Hogares en México (Primera) (Spanish) [Mexican families (first)] [Internet]. Aguascalientes: INEGI; 1997. Available from: https://en.www.inegi.org.mx/contenidos/productos/prod_serv/contenidos/espanol/bvinegi/productos/historicos/21 04/702825491697/7028254916971.pdf.

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística Geografía e Informática. XII Censo General de población y Vivienda 2000 (INEGI) (Spanish) [XII general census of population and housing 2000 (INEGI)]. Aguascalientes: INEGI; 2000.

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística Geografía e Informática. Principales resultados del censo del censo de población y vivienda 2010 (INEGI) (Spanish) [Main census results of the 2010 population and housing census (INEGI)]. Aguascalientes: INEGI; 2011.

- Jiménez Pérez J, Cuéllar G, Treviño E. Áreas verdes del municipio de monterrey (Spanish) [Green areas in the city of Monterrey]. Monterrey: Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León; 2013.

- Municipio de Durango. Plan director de forestación urbana del municipio de Durango (Spanish) [Urban afforestation master plan for the municipality of Durango]. Durango: Gaceta Municipal; 2006. p. 41.

- Secretaría del Medio Ambiente. Plan verde de la Ciudad de México: 5 años de avances (Spanish) [Mexico City green plan: 5 years of progress]. Ciudad de México: Sedema; 2012.

- Secretaría del Medio Ambiente. Sustainable CDMX: Green, mobile, educational, recreative. Ciudad de México: Sedema; 2015.

- Secretaría del Medio Ambiente. NADF-001-RNAT- 2015 [Internet]. 2015. Available from: http://www. paot.org.mx/centro/normas_a/2016r/NADF-001-RN AT-2015_PODA_DERRIBO_TRASPLANTE_01_04_2016.pdf.

- Secretaría del Medio Ambiente. Ciudad verde, Ciudad viva (Spanish) [Green city, living city] [Internet]. 2016. Available from: http://data.sedema.cd mx.gob.mx/sedema/index.php/ciudad-verde.

- Secretaría del Medio Ambiente. Programa de Reforestación Urbana (Spanish) [Urban Reforestation Program] [Internet]. 2017. Available from http://data. sedema.cdmx.gob.mx/reforestacion-urbana/index. html.

- UN-Habitat III. Urbanization and development. Nairobi: UN-Habitat; 2016.

- Fernández-álvarez R. Inequitable distribution of green public space in the Mexico City: An environmental injustice case. Economía, Sociedad y Territorio 2017; 42(54): 399–428.

Supporting Agencies

Copyright (c) 2021 G. Maldonado-Bernabé, A. Chacalo-Hilu, I. Nava-Bolaños, RM Meza-Paredes, AY Zaragoza-Hernández

License URL: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0

This site is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0).

Chinese Academy of Sciences, China

Indexing & Archiving

Asia Pacific Academy of Science Pte. Ltd. (APACSCI) specializes in international journal publishing. APACSCI adopts the open access publishing model and provides an important communication bridge for academic groups whose interest fields include engineering, technology, medicine, computer, mathematics, agriculture and forestry, and environment.

.jpg)

.jpg)