Urban sustainability: Analysis on urban scale of Temuco Chile

Vol 2, Issue 1, 2021

Download PDF

Abstract

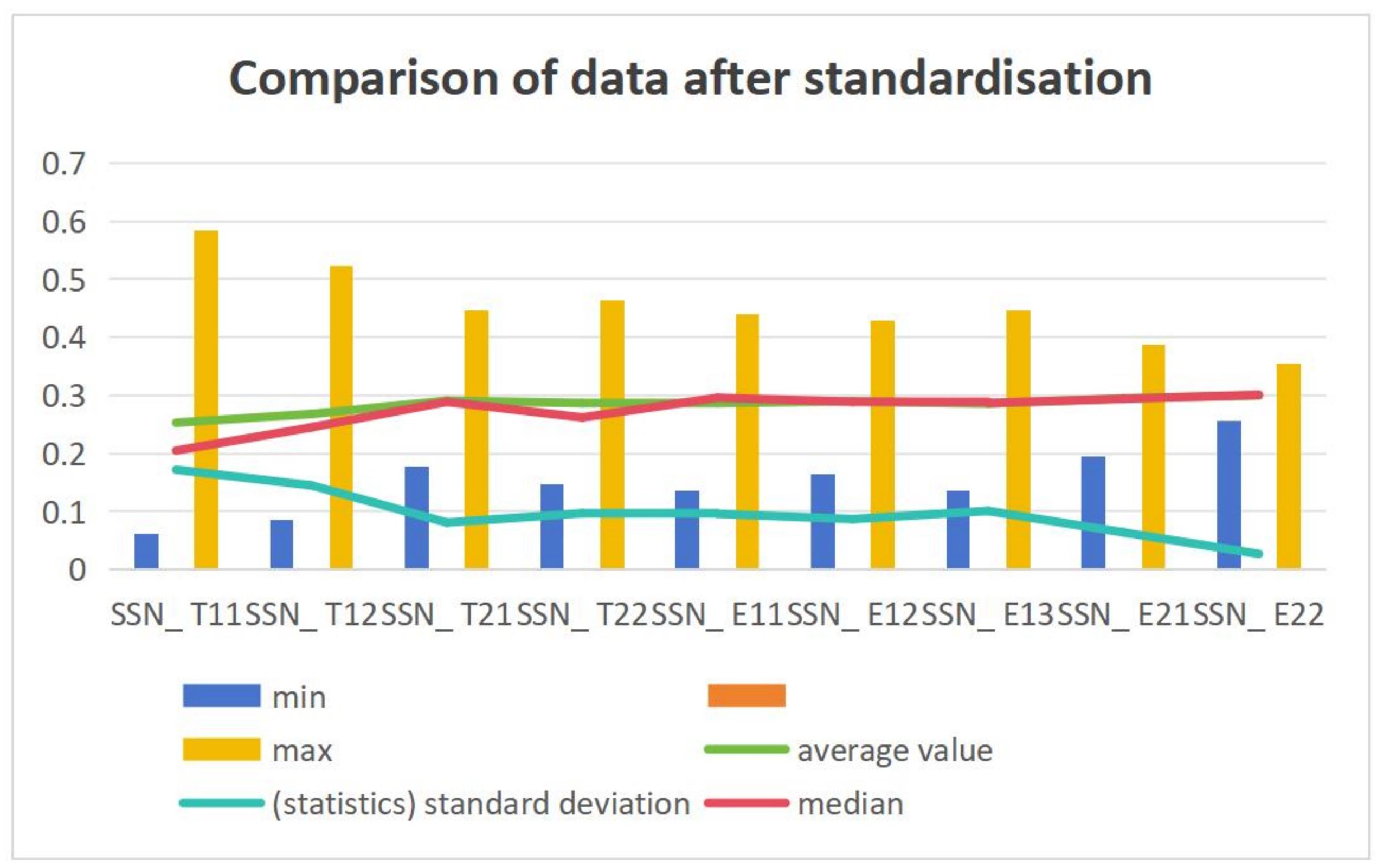

Cities develop in an excessive and disorderly way, losing their original characteristic identity and function. As a response to the deconstruction of the city, sustainable urban design came into being. This study evaluated the performance and sustainability level of Temuco community. The study was conducted in four sectors of the city, which are symbols and representatives of different stages of urban expansion. Through a set of urban design index standards including economic, social and environmental variables, the development of the community and the quality of life of its residents are evaluated. The results show that the Abraham Lincoln community has a better sustainability index, gathering a group that encourages sustenance and the availability of necessities nearby. The study found that new and old neighborhoods have deficiencies in neighborhood sustainability.

Keywords

References

- Mostafavi M, Doherty G. Ecological urbanism. Barcelona: Gustavo Gili, SL; 2014. p. 656.

- Nunes MFO, Mayorga CT, Gullo MCR, et al. Indicators of urban sustainability: Their employment in two neighborhoods of Caxias do Sul. Arquiteturarevista 2016; 12(1): 87–100.

- Catumbarincón-Rincón C. Construction of common and collective spaces: Conceptual contributions to urban territory. Bitacora Urbano Territorial 2016; 26(1): 9–22.

- Winchester L. Desafíos para el desarrollo sostenible de las ciudades en América Latina y El Caribe (Spanish) [Challenges to sustainable urban development in Latin America and the Caribbean]. Revista Latinoamericana de Estudios Urbano Regionales 2006; 32(96): 7–25.

- Caravaca I, González G, Silva R. El Papel de las ciudades en el desarrollo sostenible: El caso del programa ciudad 21 en Andalucía, España (Spanish) [The role of cities in sustainable development: A case study of citizen agenda 21 in Andalusia, Spain]. Revista Latinoamericana de Estudios Urbano Regionales 2005; 31(94): 5–24.

- Llamas-Sánchez R, Muñoz-Fernández Á, Maraver-Tarifa G, et al. El Papel de las ciudades en el desarrollo sostenible: El caso del programa ciudad 21 en Andalucía (Spanish) [The role of cities in sustainable development: A case study of citizen Agenda 21 in Andalusia]. Revista Latinoamericana de Estudios Urbano Regionales 2010; 36(109): 63–88.

- Baldó J. Como los espacios públicos hacen funcionar las ciudades (Spanish) [How public spaces make cities work]. Anales Venezuela Nutrición 2014; 27(1): 193–201.

- Simioni D, Jordán R, Balbo M. La ciudad inclusive (Spanish) [City including]. Santiago: CEPAL; 2003. p. 305.

- Lerner J. Acupuntura urbana (Spanish) [Urban acupuncture]. Rio de Janeiro: Editora Record; 2003. p. 137.

- Verdaguer C. De la sostenibilidad a los ecobarrios. Documentación Social (Spanish) [From sustainable development to ecological community. Social documents]. Documentación Social 2000; 119(12): 59–78.

- Zumelzu A. Urban from and sustainability: Past, present and challenge. A revision. Revista AUS 2016; 20: 77–85.

- Tapia R. Criterios para definir el concepto de barrio. Implicancias metodológicas y de política pública (Spanish) [Criteria to define the concept of neighborhood. Methodological and public policy implications]. Crimen y Violencia Urbana 2009.

- Castillo H, Herrera J. Evaluación de ecobarrios en Europa y su posible traslación al contexto Latinoamericano. Caso de la ciudad de Santo Domingo (Spanish) [European eco community assessment and its possible transformation into a Latin American context. The case of Santo Domingo]. 12th N-Aerus Conference 2011; 2011 Oct 20–22; Madrid. Madrid: Faculty of Architecture at Universidad Politecnica de Madrid; 2011. p. 13.

- Ayuntamiento de Málaga. Agenda 21: Indicadores de sostenibilidad 2010 (Spanish) [Agenda 21: Sustainability Indicators 2010]. Malaga: Observatorio de Medio Ambiente Urbano, OMAU; 2010. p. 232.

- Cabrera-Jara NE, Orellana-Vintimilla DA, Hermida-Palacios MA, et al. Assessing the sustainability of urban density. Indicators in the case of Cuenca (Ecuador). Bitácora Urbano Territorial 2015; 25(2): 21–34.

- Eltit VXE. Non-motorized urban transport: The potential of bicycle in Temuco. Revista INVI 2011; 26(72): 153–184.

- Ministerio de vivienda y urbanismo. Datos demográficos, Observatorio Urbano (Portuguese)[Demographic data, urban observatory ][Internet]. 2017 May 10. Available from: http://observatoriourbano.minvu.cl/indurb/wp_index.asp.

- Speck J. La ciudad para caminar (Spanish) [The city for walking] [Internet]. 2017 Jul 8. Avaiable from: https://www.ted.com/speakers/jeff_speck.

- Reyes S, Figueroa I. Distribución, superficie y accesibilidad de las areas verdes en Santiago de Chile (Spanish) [Distribution, area and accessibility of green space in Santiago, Chile]. Revista Latinoamericana de Estudios Urbano Regionales 2010; 36(109): 89–110.

- Burden A. Como los espacios públicos hacen funcionar las ciudades (Spanish) [How public spaces make cities work] [Internet]. 2017 Apr 2. Available from: https://www.ted.com/talks/amanda_burden_how_public_spaces_make_cities_work?language=es.

- Romero H, Vásquez A. El crecimiento espacial de las ciudades intermedias chilenas de Chillán y Los Angeles y sus impactos sobre la ecología de paisajes urbanos (Spanish) [The spatial growth of the Chilean intermediate cities of Chillan and Los Angeles and their impacts on the ecology of urban landscapes]. In: Lemos G, Ross J, Luchiari A (editors). América Latina: Sociedade e meio ambiente. São Paulo: Expressão Pulupar; 2019. p. 109–138.

Supporting Agencies

Copyright (c) 2021 Roberto Moreno García, Laura Inostroza Seguel

License URL: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0

This site is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0).

Chinese Academy of Sciences, China

Indexing & Archiving

Asia Pacific Academy of Science Pte. Ltd. (APACSCI) specializes in international journal publishing. APACSCI adopts the open access publishing model and provides an important communication bridge for academic groups whose interest fields include engineering, technology, medicine, computer, mathematics, agriculture and forestry, and environment.

.jpg)

.jpg)